Greek fire was a devastating incendiary weapon used by the Byzantine Empire during medieval times. Its origin and composition remain a mystery, as the formula was a closely guarded secret, and only a few historical accounts mention its use.

However, it was not the only incendiary weapon used in ancient times. In fact, flaming arrows, vessels of pitch, and mixtures of naphtha, sulfur, and charcoal have been utilized in battles since ancient times.

However, all other incendiary weapons pale compared to the Greek fire, which remains one of the most devastating weapons of antiquity.

What Was the Greek Fire?

Greek fire was an incendiary weapon primarily used by the Byzantine Empire starting in 672.

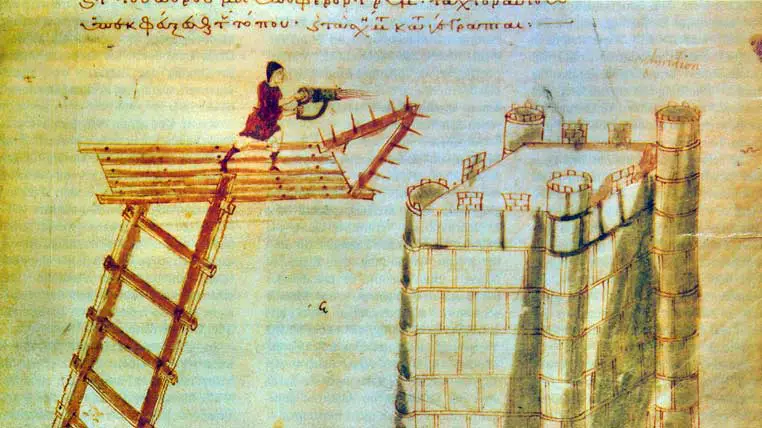

The flammable substance that generated Greek fire could be scattered with clay pots (similar to modern grenades), discharged through tubes (mainly used during sieges to throw the substance over enemy soldiers trying to scale city walls), or thrown at considerable distances using pressurized nozzles (similar to modern flamethrowers).

According to historical sources, Greek fire was highly flammable and could even ignite upon contact with water.

Some historians speculate that the compound contained a mixture of petroleum-based and pitch compounds, which made it highly combustible and nearly impossible to extinguish.

The use of Greek fire was critical to the defense of Constantinople, as it helped the Byzantines repel several sieges by foreign invaders, including the Arab Muslims and the Rus Vikings.

The Byzantines also used Greek fire in naval warfare, where the fiery substance was discharged from boats to set enemy ships ablaze.

The Crusaders from Western Europe were so impressed by Greek fire that they applied the name to any type of incendiary weapon, including those used by Arabs, Chinese, and Mongols.

Although the term “Greek fire” rapidly spread and became the primary term for the Byzantine secret weapon, it was also referred to by other names such as “sea fire,” “Roman fire,” “war fire,” or “liquid fire.”

A Devastating Weapon of Mysterious Origins

One of the earliest accounts of a “fire that could not be extinguished” can be traced back to Homer, the father of history. In his work Iliad, he narrates how the Trojans employed an unquenchable fire to destroy the vessels of the Achaeans.

The use of incendiary substances is also mentioned by the ancient Assyrians, who utilized a mysterious chemical compound to moisten the tips of arrows. These arrows were then lit and shot at enemy cities, resulting in rapidly spreading fires that were impossible to extinguish.

During the siege of Delium in 424 BC, fought during the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Boeotia, the citadel’s defenders repelled the attackers by using “fire-throwers.”

According to the ancient historian Thucydides, the Greco-Roman civilization had knowledge of a unique mixture based on petroleum, sulfur, and other undisclosed chemicals, which was successfully used in the wars of the time.

Most of the information about Greek fire comes from the chronicler Theophanes the Confessor, who mentions a formidable weapon – the liquid fire – in his writings.

Theophanes refers to the reign of the Byzantine emperor Constantine IV Pogonatus (665-685), who successfully used Greek fire in defense of Constantinople during the first (674-678) and second (717-718) siege of the Arab Muslims, thereby ensuring the empire’s survival.

Theophanes credits the invention of Greek fire to Callinicus (or Kallinikos), a craftsman and architect from Heliopolis.

When the Arabs besieged the city, Kallinikos was compelled to flee with his family and seek refuge in Constantinople. Among the items Kallinikos took with him was the recipe for a highly flammable chemical compound.

Kallinikos later offered the secret of Greek fire to the Byzantine emperor Constantine IV Pogonatus, who achieved resounding victories against the Muslim besiegers using this new weapon.

However, some researchers today dispute the writings of Theophanes the Confessor, considering it impossible for a single individual to have discovered such a complex chemical compound due to its complexity.

In reality, Kallinikos may have found the formula in a manuscript from the Library of the School of Chemistry in Alexandria.

Another interesting story can be found in the work of Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Administrando Imperio, where we read how he instructed his son, the future Emperor Romanus II, not to divulge the secret of the formula of Greek fire to anyone.

According to Porphyrogenitus, an angel bestowed the recipe for Greek fire upon the first Christian Emperor, Constantine the Great. It was also stated that the secret to creating this incendiary weapon could only be shared among Christians within the walls of the Holy City.

Anyone who violated this divine decree by revealing or betraying the secret recipe would face harsh consequences.

According to Porphyrogenitus, a treacherous officer bribed by the empire’s enemies tried to divulge the recipe for Greek fire but was immediately struck by a bolt of lightning upon entering the church.

This intriguing story adds to the mystique of Greek fire and reinforces the belief that the secret formula was a precious commodity that had to be protected at all costs.

Theories Regarding the Greek Fire Secret Formula

The composition of Greek Fire remains a matter of speculation and debate, with various proposals, including combinations of pine resin, naphtha, pitch, calcium phosphide, sulfur, or niter.

For a long time, the most popular theory regarding the composition of Greek fire was that its main ingredient was saltpeter, making it an early form of gunpowder.

This view was based on the “thunder and smoke” description and the distance the flame could be projected from the siphon, which suggested an explosive discharge.

However, this hypothesis has been refuted since saltpeter was not used in warfare in Europe or the Middle East before the 13th century and is absent from the accounts of the Muslim writers before the same period.

Another idea proposed that the inextinguishable nature of Greek fire by water suggested its destructive power was due to the explosive reaction between water and quicklime.

However, literary and empirical evidence refute this theory.

Greek fire was often poured directly onto the decks of enemy ships, and Emperor Leo’s Tactica suggests that contact with water was not necessary for the substance’s ignition.

Additionally, experiments show that the result of the water-quicklime reaction would be negligible in the open sea.

A similar proposition suggested that Greek fire was made of calcium phosphide, which releases phosphine in contact with water, igniting spontaneously.

However, experiments with calcium phosphide also failed to reproduce the described intensity of Greek fire.

Most modern scholars agree that Greek fire was based on either crude or refined petroleum, comparable to modern napalm.

The Byzantines had easy access to crude oil from the naturally occurring wells around the Black Sea or in various locations throughout the Middle East.

The availability of naphtha, a crude oil called “Median oil” by the Greeks and “naft” by the Arabs, as an essential ingredient of Greek fire seems to be corroborated by historical records.

Resins were probably added as a thickener to increase the flame’s duration and intensity. Pine tar and animal fat were also included in a modern theoretical concoction and other ingredients.

A 12th-century Arab version of Greek fire called naft was recorded by Mardi bin Ali al-Tarsusi for Saladin. It also had a petroleum base, with sulfur and various resins added.

An Italian recipe from the 16th century included coal from a willow tree, alcohol, incense, sulfur, wool, camphor, burning salt, and pergola. The concoction was guaranteed to “burn underwater” and to be “beautiful.”

The Formula Mysteriously Disappears

Greek fire was a weapon successfully used for almost 500 years until the Fourth Crusade in the late 12th century, which resulted in the conquest of Constantinople by Christian armies from the West.

The last recorded possible use of Greek fire dates back to 1203 when, according to old texts, the Byzantines loaded 18 war vessels with barrels containing a flammable liquid, possibly Greek fire.

They directed the liquid in a desperate attempt to destroy the fleet of Christian ships sailing from Galata. However, the Byzantine strategy was a failure.

Subsequently, the formula for Greek fire completely disappears from historical records.

Specialists believe that there are several reasons for this:

- The Byzantine Empire lost access to the raw materials necessary to prepare the formula. After the Arabs conquered most of the Asian territories, especially those between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, the Byzantines could no longer obtain the necessary ingredients.

- The chemists who knew how to prepare the formula were either killed or had to flee from the Crusaders who occupied Constantinople for 57 years.

- The decline of the Byzantine Empire, which from the 13th century controlled only a few fragmented territories.

- In the 14th century, Sultan Murad II used a rudimentary form of Greek fire during the failed siege of Constantinople. The formula used by the Ottomans was clearly different from that used by the Byzantines.

This new formula created by the Ottomans spontaneously ignited, like Greek fire. However, the flames were not as violent, the ignition was not accompanied by a “thunderous” noise, and the fire could be extinguished with water.

A similar recipe was used a few decades later, in 1430, by Sultan Mehmed II. His armies used a unique mixture, which probably contained gunpowder.

But unlike Greek fire, which could be easily controlled by those who knew its secrets, this new formula was volatile and dangerous.

The mixture was used for a very short time, and it was quickly replaced after a series of uncontrolled explosions killed several hundred Ottoman soldiers.

A 1,300-Year-Old Enigma

According to the Byzantine emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, the secrecy surrounding the Byzantine fire formula was exceptionally high.

Manufacturing the inflammable liquid involved many people, ranging from pottery masters to some of the most distinguished chemists of the time. However, no one outside the emperor knew the entire formula or all the stages of combining the ingredients.

Greek fire was a powerful weapon that significantly impacted the enemy’s morale and remained crucial to the Byzantine Empire for centuries.

The explosions, the intensity of the flames, and the dense, suffocating smoke created a terrifying image of the battlefield.

Nevertheless, Greek fire had limitations compared to more traditional forms of artillery. For instance, its siphon version had a restricted range of action and could only be safely used on calm seas with favorable wind conditions.

From the 15th century onwards, liquid fire and inflammable materials were gradually abandoned with the widespread use of gunpowder and firearms.

However, these weapons experienced a new period of glory in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Molotov cocktails, homemade bombs, and other inflammable devices are advanced forms of liquid fire that the Byzantines used with great success during the Middle Ages.

The secret formula has been preserved and continues to fascinate and intrigue generations of researchers.

A team of scientists conducted an experiment in a final demonstration of the destructive power of Greek fire. They reproduced several formulas based on the historical information available and the testimonies of those who observed how Greek fire behaved.

One of the formulas proved very close to reality – a compound of oil, resins, gasoline, and other ingredients.

The researchers projected the inflammable liquid to a distance of almost 65 feet (about 20 meters) using a pressurized nozzle system identical to the one used by the Byzantines in the seventh century.

The substance ignited upon contact with water, releasing thick smoke. The flames quickly spread, and the recorded temperature exceeded 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius).

At Ancient Theory we only use trusted sources to document our articles. Such relevant sources include authentic documents, newspaper and magazine articles, established authors, or reputable websites.

- Christopher McFadden - Greek Fire: The Byzantine Empire's Secret Weapon of Mass Destruction.

- Greek fire. wikipedia.org. [Source]

- Nicholas D. Cheronis - Chemical Warfare in the Middle Ages: Kallinikos' 'Prepared Fire'. Journal of Chemical Education, Chicago, 1937.

- James Riddick Partington - A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

- The mystery of Greek fire. heritagedaily.com.

- Alex Roland - Secrecy, Technology, and War: Greek Fire and the Defense of Byzantium, 678-1204. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

- Philip Chrysopoulos - Greek Fire: The Weapon that Protected the Byzantine Empire. greekreporter.com.

- Karen Harris - Greek Fire: What Was This Powerful Ancient Weapon? historydaily.org.