Poseidon was assigned sovereignty over the waters when the universe was partitioned among the gods, while his brother Zeus was granted the sky and Hades the Underworld.

His most potent weapon, the trident, originally symbolized the creation of waves and lightning, much like Zeus’ thunderbolt.

In Roman mythology, the deity Neptune serves as the counterpart to Poseidon.

Etymology

The god of the sea has been present in Greek religion since ancient times, and his name has been known since the Mycenaean period (c. 1600-1100 BC).

Initially written in a script called Linear B, which preceded the Greek alphabet, the god appears in Mycenaean texts under the name Posedao or Posedawone. Thus, the term “Poseidon” likely has roots in two different words.

The first is the Greek term posis, derived from the Proto-Indo-European root pótis, both of which mean “husband,” “lord,” or “master.”

The second linguistic element that makes up the god’s name is subject to some uncertainty. One interpretation suggests that it could come from the root da, which means “earth.” This would make “Poseidon” translate to “Lord of the Earth” or perhaps even “Husband of the Earth.”

Regarding his name, one possible translation links it to Demeter, the Earth goddess. Early Greek Mycenaean references imply an intimate connection between Poseidon and Demeter, and perhaps between Poseidon and Persephone.

An alternative interpretation ties the name to the term dâwon (traditionally meaning “water”), rendering “Poseidon” as “Lord of the Waters.” This theory connects the god’s name to his domain of authority—the sea.

However, the assumption that “Poseidon” has a direct connection to the ocean, water, or sea may be misleading, as no early Mycenaean references suggest such a link.

In fact, many linguists today consider the god of seas’ name to have pre-Greek origins and potentially be non-Indo-European.

Characterization

Poseidon was as untamable as the seas he purportedly governed. A catalyst and an insurgent, the god of the oceans played a significant role in Greek mythology due to his ongoing opposition to Zeus’ complete control of the pantheon.

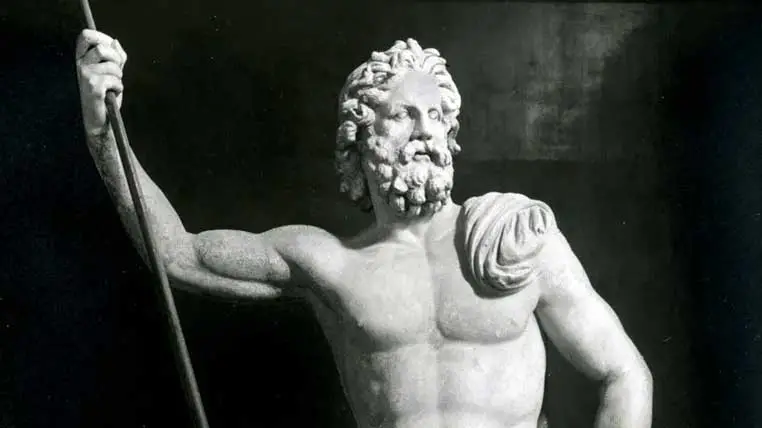

He is typically depicted as a mature, sturdy, bearded god wielding a trident—a three-pronged spear that he wielded in battle, commanded the sea with and used to cause catastrophic earthquakes.

In the Iliad and the Odyssey, the ruler of the seas and oceans is portrayed as an ever-present disruptive force. He was known to meddle in the affairs of gods and ordinary mortals, often with dramatic outcomes.

Due to his fearsome reputation, he became a symbol of a turbulent, treacherous sea that could claim innocent lives at any moment.

As the god of horses, Poseidon is often portrayed riding a chariot pulled by hippocampi—half-horse, half-snake creatures that glide over the waves. He is also associated with other animals on both land and sea, including dolphins, sea horses, and bulls.

In addition to his dwelling on Mount Olympus, the god of seas owns beautiful underwater palaces adorned with coral, pearls, and precious stones. He also maintains a magnificent stable of horses and numerous herds of horses throughout Greece.

Despite his fickleness, the god of the seas engaged in numerous romantic relationships with goddesses, nymphs, and mortal women, but only fathered monsters and bandits.

Genealogy

Regarding his family tree, Poseidon’s parents were Cronos and Rhea. His siblings include Zeus, Hades, Hera, Demeter, Hestia, and Chiron.

He had multiple wives and lovers, including Amphitrite, Aethra, Aphrodite, Demeter, Eurynome, Euryale, Gaia, Iphimedia, Medusa, Phoenice, and Tyro.

Poseidon and Amphitrite had three children together: the siren Triton, Bentezicim, and Rhodes—the patron goddess of Rhodes and the future wife of the god Helios.

Like many other male gods, Poseidon had numerous extramarital affairs.

Some of his most famous illegitimate descendants include Theseus, Aloadae, Antaeus, Arion, Bellerophon, Chrysaor, Neleus, Orion, Pegasus, and Polyphemus.

From his relationship with his grandmother Gaea, the god fathered two children.

The first was the giant Antaeus, who fought Heracles during the Twelve Labors. The second was Charybdis, a sea monster that lurked in the deep waters of the Strait of Messina, creating massive and merciless whirlpools that swallowed unsuspecting travelers and merchants.

Among his lovers were Aphrodite and his own sister Demeter. Several children were born from his union with Demeter, including a talking horse named Arion.

Finally, Poseidon raped Medusa in Athena’s temple, resulting in the birth of two other legendary creatures: the winged horse Pegasus and the giant Chrysaor, both of which emerged from Medusa’s throat after the hero Perseus beheaded her.

In addition to his dealings with goddesses, he also courted numerous nymphs, such as Thoosa, who gave birth to the fearsome cyclops Polyphemus.

However, Poseidon’s escapades did not end there.

He also pursued mortal women, resulting in the birth of heroes and other mythical personalities, including Tezeu, Otus, Ephialtes, Bellerophon, Pelias, Neleus, Orion, and Proteus, who could change his form.

The sea god’s sons, Minyas and Boeotus, founded several settlements in the central region of Boeotia, while Aeolus established the city of Eolia. Eumolpus, another son of Poseidon, was a renowned Thracian king who waged war against the Athenians.

Myths and Legends

Poseidon was present in many Greek myths, especially those involving the sea or water. He was often depicted as an influential figure, wielding a trident and riding a chariot pulled by sea creatures.

He was sometimes portrayed as a benevolent god, helping seafarers and fishermen, but he could also be vengeful and wrathful, punishing those who angered him.

Some famous myths associated with Poseidon include his rivalry with Athena over the patronage of Athens, his creation of the first horse, his role in the founding of the city of Corinth, and his involvement in the epic journey of Odysseus.

Birth

The story of Poseidon’s birth is steeped in Greek mythology. According to the standard version, he was the fifth child of Cronus and Rhea, born after Hestia, Demeter, Hera, and Hades in that order.

Cronus feared that one of his children would overthrow him, just as he had done to his father, so he devoured each newborn.

He was the last to suffer this fate before Rhea intervened. She saved Zeus and Poseidon by tricking Cronus into eating a rock wrapped in a blanket instead.

When Zeus grew up, he gave his father a powerful emetic that made him regurgitate the children he had eaten.

Armed with a trident forged by the Cyclopes, Poseidon helped his siblings and other divine allies defeat the Titans and take over as rulers.

Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades drew lots to divide the world between them. Zeus got the sky, Poseidon the sea, and Hades the underworld, as told by Homer and Apollodorus.

In a rarer and later version, the god avoided being devoured by his father because Rhea saved him in the same way she did Zeus. She offered Cronus a foal instead, claiming she had given birth to a horse instead of a god.

Rhea entrusted her baby to a spring nymph named Arne, who denied having him when Cronus demanded the child. The nymph’s spring thereafter was named Arne, which sounds like the Greek word for ‘deny.’

Poseidon and Amphitrite

Poseidon and Amphitrite is a Greek myth about the marriage of the god of the sea, and the sea goddess, Amphitrite.

According to the myth, Poseidon was wandering the earth when he came upon the beautiful Nereid (sea nymph) Amphitrite. He was immediately struck by her beauty and asked her to marry him.

However, Amphitrite was not interested in marrying him and fled to the Atlas Mountains to escape his advances.

Determined to win her over, he sent a dolphin to find her and convince her to return to him. The dolphin successfully found Amphitrite and convinced her to marry Poseidon.

In some versions of the myth, the dolphin is said to have been sent by the god of love, Eros, to help Poseidon win Amphitrite’s heart.

Eventually, Amphitrite agreed to marry Poseidon, and they had many children together, including Triton, a merman who would later become the herald of the sea.

The Conspiracy Against Zeus

The myth of Poseidon, Athena, and Hera plotting to deceive and bind Zeus to his throne is known as the “Homeric Hymn to Hermes.”

In this myth, Hermes is born and immediately shows his cleverness by stealing Apollo’s cattle. Zeus is impressed with Hermes’ cunning and makes him a god.

Poseidon, Athena, and Hera plan to trick Zeus into celebrating Hermes’ ascension to godhood. Athena suggests they offer Zeus a large throne made from the finest materials as a gift but secretly bind him to it with unbreakable bonds.

However, Poseidon hesitates to follow the plan and suggests they honor Zeus with a smaller, more modest throne. Athena and Hera ignore Poseidon’s advice and go ahead with their plan.

When Zeus sits on the throne, he realizes he’s been tricked and becomes angry. Hermes tries to calm Zeus down, but Zeus threatens to throw him off Olympus. In the end, Hermes uses his wit to free Zeus from the bonds and earn his favor.

Poseidon Fights Athena

According to Greek mythology, Poseidon and Athena both sought to become the patron deity of the city of Athens.

As the god of the sea offered the city the gift of a spring of salt water, which was not very useful to the Athenians. On the other hand, Athena offered the gift of an olive tree, which provided food, oil, and wood, and was highly valued by the people of Athens.

In order to determine which god would become the city’s patron, a contest was held.

Poseidon struck the ground with his trident, and a spring of salt water gushed forth. Athena then hit the ground with her spear, sprouting an olive tree. The Athenians chose Athena’s gift, which was more valuable to them, and she became the city’s patron goddess.

The god was angered by this decision and, in some versions of the myth, sought revenge by unleashing a sea monster to attack Athens. However, Athena defeated the beast and continued to protect the city as its patron deity.

The olive tree that Athena had planted on the Acropolis became a symbol of Athens and the Athenians. The city became one of the most important cultural centers of ancient Greece.

The Walls of Troy

According to another Greek legend, Poseidon (along with Apollo) aided Laomedon, the king of Troy, in constructing the mighty fortifications of his city.

This task was supposedly commissioned by Zeus as a punishment for Poseidon and Apollo’s role in the Olympians’ revolt against him.

He fulfilled the work according to the instructions, but the humiliation he had endured only stoked his resentment against Zeus. When Laomedon refused to pay for the impressive walls encircling Troy, Poseidon sent a monstrous sea creature to destroy the city.

Heracles slew the monster, but the proud king failed to learn from his prior experience.

Once again, he attempted to escape paying for the hero’s services and was cruelly avenged by Heracles, who pillaged Troy and took Laomedon’s daughter, Hesione, as a captive.

The Trojan War

Like many other Olympians, Poseidon was also involved in the Trojan War, the bloody conflict between the united armies of Greece and the imposing city of Troy.

This ten-year war was sparked by the Trojan prince Paris abducting Helen, the wife of the Greek king Menelaus. In the conflict, the god of the seas and oceans sided with the Greeks.

In Homer’s Iliad, which narrates the fateful last weeks of the Trojan War, Poseidon intervened several times to aid the Greeks.

In a pivotal moment of the battle, when the Achaeans seemed all but defeated by the Trojan soldiers, Poseidon appeared on the battlefield in the guise of the prophet Calchas.

He took on this guise to avoid possible punishment from Zeus, who had decreed that no gods should interfere in the conflict between mortals.

His dramatic entrance onto the battlefield is vividly depicted in the Iliad:

Immediately afterward, he descended from the mountain slope, striding swiftly, and the lofty mountains and dense forest trembled beneath the immortal feet of Poseidon.

He stepped thrice, and with his fourth step, he reached his destination, Aegae, where his famous, shimmering, golden, immortal palace was built in the depths of the sea.

He harnessed two horses with bronze hooves, swift in flight, with flowing golden manes, and he clad himself in gold, grasping the expertly crafted golden whip, and set out over the waves.

Then the sea creatures frolicked everywhere in the depths, for they knew their master well, and the sea parted joyfully before him.

Despite Poseidon’s assistance, the Greeks suffered significant losses, leading Agamemnon, the army’s commander, to order a retreat.

Once again, he intervened, this time with the help of Hera, who distracted Zeus with her feminine charms and lured him into a deep slumber.

Taking advantage of the opportune moment, Poseidon revealed his true identity and assumed command of the army for a devastating assault.

However, the god’s furious roars awoke Zeus, who, upon seeing the destruction wrought by his brother, ordered him to immediately withdraw from the fight.

Poseidon obeyed, not out of fear but out of respect for the Father of Olympus, as he declared.

Ulisse and the Cyclop

After the fall of Troy, the god of the seas turned his wrath towards Ulisse, the Greek hero immortalized in Homer’s Odyssey for his long journey home.

Although Ulisse fought on the side of the Achaeans, a fateful incident caused him and his crew to land on the island inhabited by Polyphemus, a Cyclops and one of Poseidon’s offspring.

Polyphemus, a man-eating monster, began hunting and devouring Ulisse’s crew members.

With only a few survivors left, Ulisse and his men devised a plan to trick the Cyclops into drinking a strong sleeping potion.

While the giant slept, Ulisse plunged his spear into Polyphemus’ single eye in the middle of his forehead, causing the monster to wake up roaring with pain and blindly searching for the perpetrator.

This daring feat allowed Ulisse to escape the clutches of the Cyclops but brought Poseidon’s wrath upon him, resulting in two failed revenge attempts by the god.

In the first instance, the god unleashed a brutal storm on Ulysses and his crew as they left Calypso’s island. The second time, he sent Charybdis, another sea monster, but this plan was also unsuccessful.

The Cult of Poseidon

The cult of Poseidon was highly venerated throughout the Greek world, with its sway particularly strong and influential in port cities such as Athens and Corinth, where numerous guilds of sailors and merchants thrived.

As the ruler of the seas and oceans, Poseidon was respected and feared by Greek sailors who were well aware of the perils they faced on their voyages.

Although primarily considered a god of the depths, Poseidon’s power extended to land, enabling him to cause devastating earthquakes and landslides.

Additionally, he was revered as a god of social relations and education.

The god of the seas was worshipped in hundreds of temples throughout ancient Greece, but the most significant places of worship were in Corinth, Helice (in Achaea), and Onchestus (in Boeotia).

An altar dedicated to Poseidon also existed in the Erechtheion of Athens, beside a saltwater spring believed to have been created by the god when he competed with Athena for the city.

Locals still claim that one of the stones near the spring bears the mark of the trident with which the god once struck it.

Most temples dedicated to the sea god were built on the coast, and the Temple of Poseidon in Sounion, located approximately 70 kilometers southeast of Athens, is a well-preserved example.

Poseidon was honored with multiple festivals, like the other gods of the Greek pantheon.

The most important of these were the Isthmian Games, one of Ancient Greece’s four major sporting events (the others being the Olympic Games and Nemean Games, both in honor of Zeus, and the Pythian Games, in honor of Apollo).

The Isthmian Games were held biennially near the great Temple of Poseidon in Corinth, where participants competed in various athletic and musical contests for the grand prize: a crown of olive leaves.

Poseidon and Neptune: A Comparison of Two Powerful Gods

The Roman equivalent of the Greek god Poseidon was Neptune.

Neptune was also the god of the sea, earthquakes, and horses in Roman mythology and was considered one of the major gods in the Roman pantheon.

There were some differences between the Greek Poseidon and the Roman Neptune.

Neptune was generally seen as a less aggressive and more peaceful deity than the god of the seas of Greek mythology, who was sometimes associated with destructive earthquakes and storms.

Additionally, Neptune was often depicted as riding in a chariot pulled by horses, while Poseidon was more commonly associated with a chariot drawn by sea creatures.

The worship of Neptune in ancient Rome was widespread, and he was often considered one of the most important gods in the Roman pantheon.

He was typically worshipped in association with other deities, such as Venus (goddess of love) or Salacia (goddess of saltwater).

Temples to Neptune were built throughout the Roman Empire, with some of the most famous in Rome, Ostia, and Tivoli. Neptune was also frequently depicted in Roman art, and his image appeared on coins and other currencies.

At Ancient Theory we only use trusted sources to document our articles. Such relevant sources include authentic documents, newspaper and magazine articles, established authors, or reputable websites.

- Poseidon. wikipedia.org. [Source]

- Robert Graves - The Greek Myths: The Complete and Definitive Edition. Penguin Books, 2017.

- Edith Hamilton - Mythology. Grand Central Publishing, 2011.

- Karl Kerenyi - The Gods of the Greeks. Thames & Hudson, 2011.

- Jennifer Larson - Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore. Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Richard P. Martin - The Language of Heroes: Speech and Performance in the Iliad. Cornell University Press, 1994.

- Walter Burkert - Greek Religion. Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Emily Katz Anhalt - Enraged: Why Violent Times Need Ancient Greek Myths. Yale University Press, 2017.

- Sarah Pomeroy - Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. Schocken, 1995.

- Christopher A. Faraone - Talismans and Trojan Horses: Guardian Statues in Ancient Greek Myth and Ritual. Oxford University Press, 1992.

- C. Scott Littleton - Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology, Volume 4. Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2005.

- Poseidon. britannica.com. [Source]

- B. C. Dietrich - The Origins of Greek Religion. Bristol Phoenix Press, 2004.

- Timothy Gantz - Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.